Le Havre: A city reborn

The port city, still held by the Nazis for more than three months after D-Day, was razed during 132 separate Allied bombing missions. Its post-war urban revival earned it a rare UNESCO designation

For a European city, Le Havre is young. Founded in 1517 to replace the nearby Seine River harbours in Honfleur and Harfleur that were becoming impassable because of silt buildup, it soon became one of France’s busiest ports for trade with the colonies. Its location on the English Channel at the mouth of the Seine made it ideal for trade in coffee, cotton and oil, among other staples.

Some 427 years later, the German-occupied city was flattened by an Allied bombing campaign, Operation Astonia, that killed 5,000 residents, injured another 80,000 and destroyed 12,500 buildings. For that, France’s president Charles de Gaulle later awarded the city the Legion of Honour for “the heroism with which it has faced its destruction.”

Ouache, as we say in Québec.

The French government decided the best way to honour the incredible sacrifices of les havrais et les havraises was to build a new city on the rubble of the old, appointing famed architect Auguste Perret, who was a major innovator in the use of reinforced concrete, to lead the urban revival.

The result was so remarkable that, in 2005, it would become one of the rare contemporary cities recognized as a World Heritage site by UNESCO. “Le Havre is exceptional among many reconstructed cities for its unity and integrity. (…). It is an outstanding post-war example of urban planning and architecture based on the unity of methodology and the use of prefabrication, the systematic utilization of a modular grid, and the innovative exploitation of the potential of concrete.”

Place de l’Hôtel de ville is typical of the approach to greenspace taken in Auguste Perret’s urban plan for the rebuilt Le Havre.

Completed in 1964, the reconstructed lower city around the port still feels fresh and modern, 60 years later. Low-rise housing complexes fronting on wide boulevards and generous greenspaces leave you feeling far removed from the core of a major European port city. Walking around on a Sunday afternoon, it felt almost deserted as, no doubt, the 170,000 residents were celebrating Mother’s Day at home.

Although Auguste Perret was responsible for planning the rebuild, only two of the buildings here are his own work: city hall, and the remarkable and unforgettable St. Joseph’s Church, a beautiful work of concrete and stained glass unlike any church I’ve seen. It’s massive 107-metre tower pokes way above the city skyline and acts as a beacon, a lighthouse, that can be seen far out to sea, day and night. Inside the cavernous church, even the altar respect the symmetry of Perret’s vision, placed in the middle of the hall rather than at its head. A monument to the 5,000 residents who died in the Allied bombings, Perret wanted it to be unique. He recruited Marguerite Huré to design the stained glass. Rather than use the typical religious iconography, she created a kaleidoscopic of colours and hues that change on each side of the hexagonal tower and can appear to change colour depending in the position of the observer. It is stunning in both its simplicity and complexity, as you can see in some of my photos.

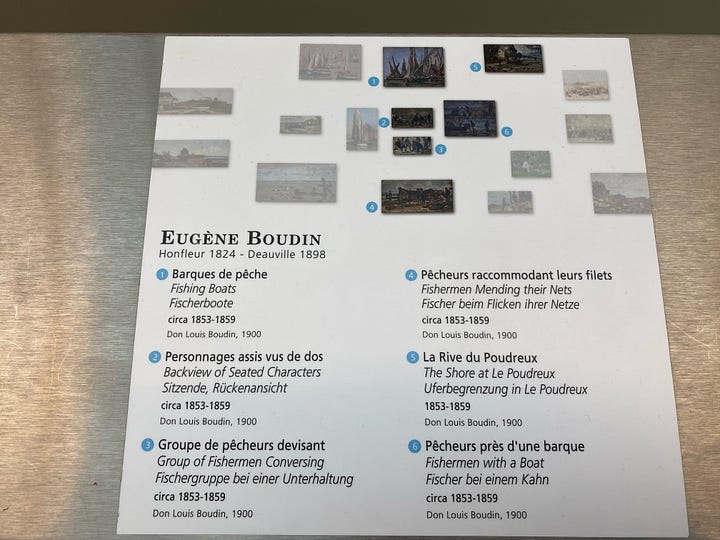

Another Le Havre building that broke with tradition is the André Malraux Museum of Modern Art. Rather than building a typical closed and darkened museum, the designers wanted a multipurpose building that took advantage of its unobstructed view facing the English Channel with floor-to-ceiling glass walls, where the flood of natural light could be controlled by a combination of louver blades on the ceiling and filters in the glass and blinds to protect the artworks from the damaging effects of direct sunlight. The museum replaced a 100-year-old predecessor, which was destroyed by the bombings. Most of its collection of statuary was lost, but an extensive collection of 1,500 paintings had been safely secured off-site. Today, the Malraux Museum has the second-largest collection of Impressionist painting in France (after the Orsay in Paris), featuring the largest collection of works by Eugène Boudin as well as other celebrated French artists, including Monet, Renoir, Gaugin and Matisse.

The multifunction building—which also houses a restaurant, boutique and a bookstore—has no interior load-bearing walls, providing an open, modular space that, like the city itself, makes you feel like you are communing with your surroundings.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to explore more of the city, the next day I was on the road again, this time to Caen, another French city that was almost levelled by the Allies in the Battle of Normandy that began with the D-Day invasion on June 6. Caen was liberated on July 19, Le Havre not until Sept. 12.