You can't play peek-a-boo with poverty

Many of our neighbours are fighting to meet the basic needs of life. Closing our eyes to their struggles won't make the problems disappear

Paris in the fall. The cold, rainy weather and the economic desperation of the hundreds of migrants selling cheap trinkets and roasted corn and nuts around the base of the Eiffel Tower can get to you. Later, you stop to observe the old man sitting cross-legged on the métro’s large exhaust grates on the Boul. de Magenta median, staring sightlessly with a satisfied grin on his face as his cold bones are warmed by the hot air from the trains below. You watch as scores of people gather at the end of the Saturday market under the elevated train tracks to scoop up discarded, damaged fruit and vegetables from the ground before city workers sweep up the detritus. You see the unhoused all over the city, at the train stations, around the churches, in the parks. It’s not new, you know that. And Paris is far from alone. You’ve seen it in Strasbourg, in Montpellier, in Toulouse. You’ve seen it in Montréal. You just read a story about your neighbours back home in Verdun fighting to keep a group of unhoused from staying temporarily in a vacant senior’s residence a few blocks from your apartment. You wish you were there to raise your voice, “if not in my backyard, then in whose?”

In Strasbourg, I stumbled across an orderly queue of tents along the banks of the Rivière Ill. They were all lined up, many the same colour and model, so I at first thought it was an encampment for pilgrims coming to visit the Église réformée Saint-Paul, just across the river. It had more the look of a scout jamboree than a tent city,

A little research back at my hostel revealed the camp had been there almost three months. The roughly 40 small tents housed about twice as many people, mostly immigrant families from as far afield as Syria, Armenia and Cuba. There were maybe 90 people in all, and a recent court judgment gave the city the power to expel them, but they were still there, a week later.

I stopped the next day to chat with one family. They are from Syria and the daughter, about 14, is able to speak some French. I’ll call her Aliyah. She explains that the municipal government, which requested the ruling, is also trying to find them a more permanent shelter. It’s a problem in Strasbourg, where the existing shelters are overflowing, rain is becoming more frequent and overnight lows are starting to dip to 11C or 12C. The judge who granted the removal order noted that the camp is at the top of a small bank with a sharp incline to the river. If a child were to slip into the cold river water….

“The fact that persons, including families with children, live in a long-term precarious health situation, exposed to public view, characterizes an unacceptable attack on their dignity,” the judge argued, according to Rue89 Strasbourg. A statement from the Strasbourg Administrative Court states that the judge also stressed “it would have been the responsibility of the Eurometropolis to engage with the city of Strasbourg, the state, or any other competent authority, so that the situation of the occupants of the premises could be assessed and they could be accommodated.”

Easier said than done, with more than 1,000 people living rough in the streets and parks of the city. The Rue89 solidarity collective even took it on itself to appeal to readers to offer accommodations for families with no place to go, since the emergency shelter service (dial 115) was only able to respond to a fraction of the demand.

Aliyah told me the families at the camp had all already contacted 115, to little avail. With the backing of the judge, the families are hopeful the city will find solutions. Meanwhile, they persevere in thin tents in a small park sloping towards the cold river.

I remind myself of Aliyah and her family as I walk around the streets of Paris, shivering but grateful for my new Eiffel Tower tuque and the fact that I can dip into a pub or restaurant or go back to a heated apartment whenever it gets too much. I can’t help wondering, tho, in this beautiful but expensive city, how many of the people I pass will sleep in the cold this night, or bundled up in a cheap apartment somewhere, huddled with extended family or crisis co-locs able to share the rent.

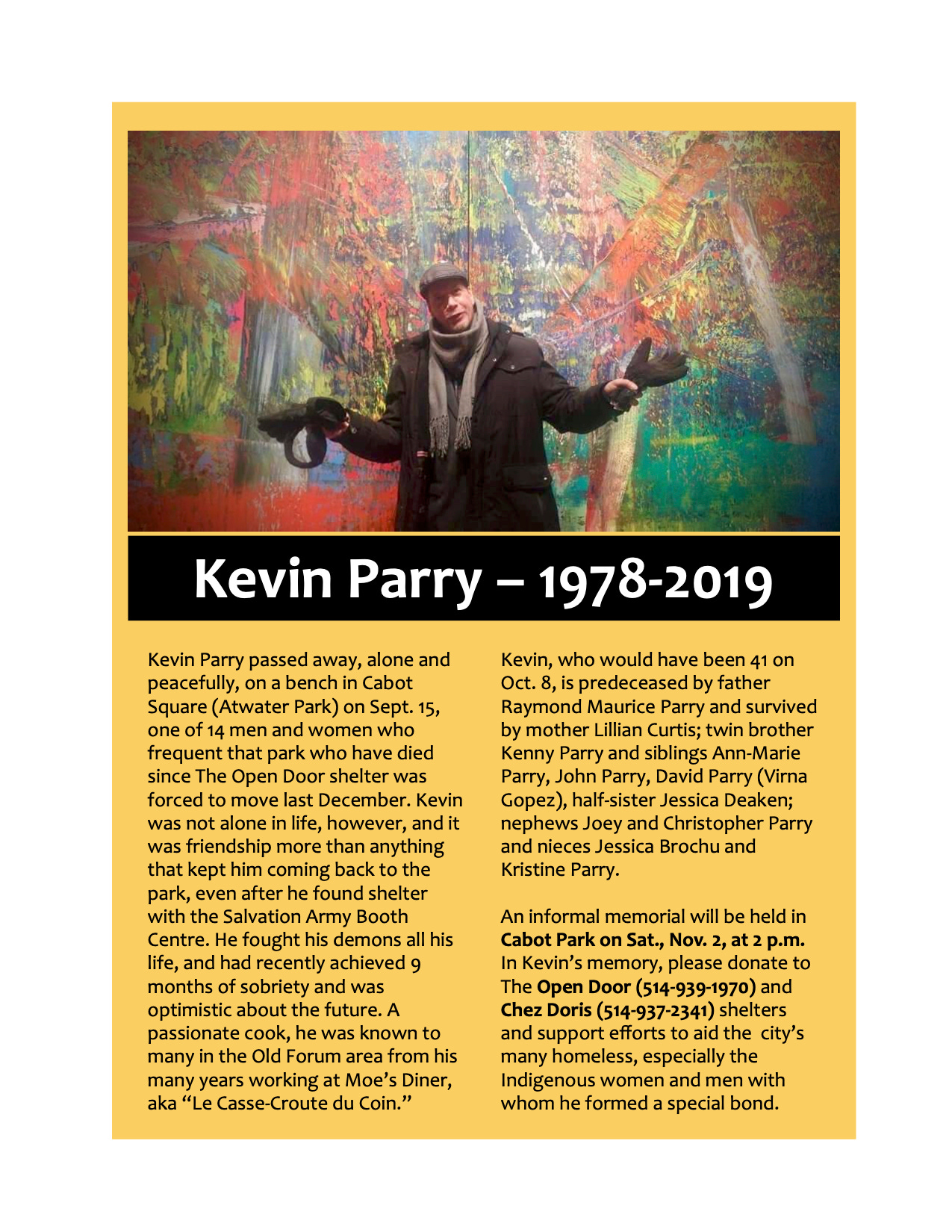

It’s not an academic question for me. Not any more. In 2019, I discovered my cousin Kevin Parry had been itinerant for many years and that his stomping grounds had been in the vicinity of the Old Forum building in Montréal. I discovered this by reading a story about how he had been found dead by a bus driver on a bench in Cabot Square.

I hadn’t seen Kevin since he was about 8 years old and knew little about what had happened since. I realized then, tho, that I could easily have passed him dozens of times on those streets near the Atwater métro, as unseen by me as all the others I hadn’t seen as they pass their days trying to keep warm or dry or fed or drunk or stoned, chased by demons or illness or addictions into a life where your only real friends are the people in the streets with you. In the tents beside you.

I spent some time with Kevin’s friends in the coming days as I tried to arrange a memorial service, four years ago this week, after seeing to his cremation. I squatted with some of them at the corner of Atwater and de Maisonneuve for a few hours and caught a small glimpse from their perspective both of how we look at them and they see us.

It has made it harder for me to not see the people in pain that are becoming an ever-growing presence on our streets and in our parks. I felt frustration and guilt as a man stopped me in front of the Gare du Nord this week and pleaded with me that he was starving. I had all my luggage with me and I’d been warned about the dangers of being robbed at this very spot, so my fear won out. I am ashamed, but at the same time I know that handing this man a few euros will not solve his problems. Even if, by some miracle, my charity helped him in any lasting way, it wouldn’t help thousands of others. I can’t feed them all, can’t house them all, can’t care for them all.

But we can. It starts, as the Strasbourg judge noted, by providing them with dignity and the essentials of life: food, shelter and human contact. We have to stop looking away as they drown in the Mediterranean or die in the jungles of Central America in a desperate attempt to find a home free of war, famine and violence. We have to stop saying “there’s no room here” when we live in societies where “room” is our biggest asset. Where jobs are begging to be filled but go begging for candidates because the natives are too proud to take them and the government too fearful to let in people who’d love the work but don’t fit the profile of the dominant culture, be it skin colour, religion or language.

We have to stop looking away. Yes, it’s not your problem. It’s our problem. Only we can solve it. We do that by having immigration policies based on compassion. The commerce will follow, as thousands of years of history have shown us. We do that by providing food and housing supports, health and social services, by giving people an opportunity to succeed rather than ensuring their failure by providing them with little but platitudes about our generosity and how they should be more grateful.

We won’t make poverty disappear by closing our eyes, we have to do it by opening them. By opening our hearts and doing the right thing. Wanna give it a try?

See you in a few days.

www.independent.co.uk /news/uk/politics/suella-braverman-tents-homeless-lifestyle-b2441565.html