Where there's a Way, there's a will

The small rural town of Moissac, France, is home to both a sacred Catholic heritage site and a little-known Second World War tale of heroism involving 500 Jewish children

I’d never heard of the French town of Moissac until I contacted my friend and former Montreal Gazette colleague Charlie Fidelman about my upcoming trip to France. Turns out she lives there part of the year with her husband, photographer Jean-Claude Teyssier.

That I hadn’t heard of it was not surprising. Even my new Toulouse acquaintances seemed unsure of where it was when I announced I was heading there for the weekend. With a population of just 13,000, Moissac makes the tourist maps mostly for its place on the French leg of the The Way of Saint James. Also known by its Spanish name, Camino de Santiago, the 770-km pilgrimage through France to the Spanish town of Santiago de Compostela is the longest and most popular of several Camino routes.

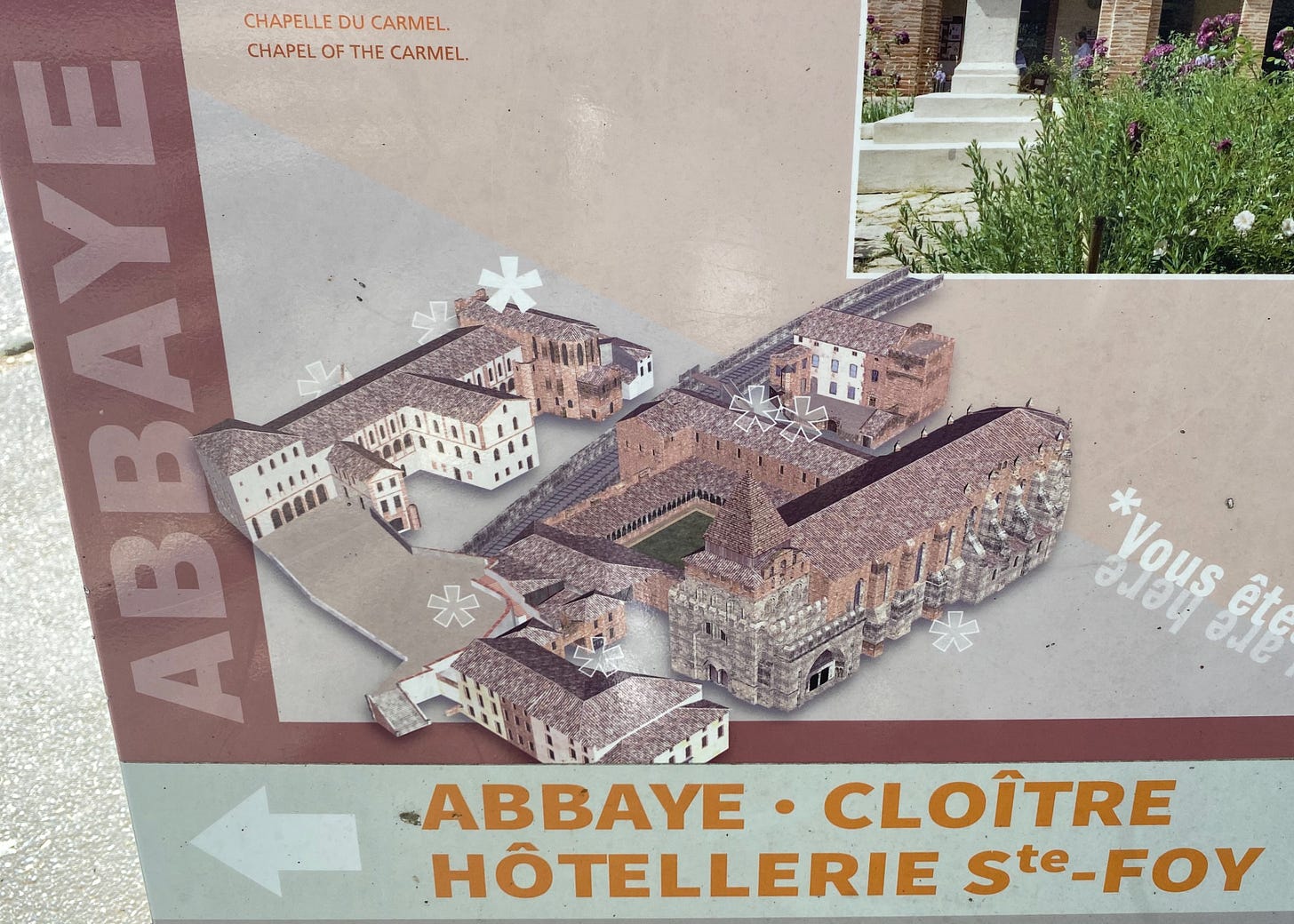

And what, pray tell, earned Moissac a treasured place on this map, which attracted 438,000 pilgrims on foot or bike in 2022? There’s little doubt that the honour goes to the Saint Pierre Abbey, originally constructed in AD 1100 for the Benedictine order of monks and which was to become a favourite of the pope, the second most important site in the order and a major power in the Catholic church.

Which also made it incredibly rich and able to collect and commission incredible works of art. Which also helped, no doubt, get it on the Camino de Santiago carte.

Things hadn’t always looked up for the local order, however. Founded in the 7th century, it was raided in turn by Moors, Norsemen, Arabs of al-Andalus, Norman pirates and in the 10th century by Hungarians.

So, you could say it was a popular tourist spot from early days, but the guests stole more than towels.

The influence and wealth of the Christian church waxed and waned over the years, but came crashing to earth following the French Revolution in 1789, when the new Constituent Assembly basically nationalized all church property. Abbeys were closed and monks expelled, treasures were seized and many church properties were converted or destroyed. But the Moissac Abbey survived. Barely.

In the railroad construction fervour of the 1840s, plans were advanced that would have razed the then long-neglected site, but it had been placed on France’s new “historical monuments” list and popular opposition helped saved much of the structures. Along with the chapel, advocates for the abbey helped preserve its (now) almost 1,000-year-old portico with its romanesque *tympanum” and its stunning cloister with its 76 capitals (the broad top of a column), 46 of which are decorated with intricate stone carvings depicting various stories from the bible.

Instead, the railroad line cut the building in two, eliminating the kitchen and dining hall but preserving the most significant heritage features, including the chapel and the cloister. Recognized as a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1998, it should be a while before anyone tries to run any more tracks through it’s belly.

But don’t judge this feisty town by the kitchen compromise forced upon it by more powerful forces. During the Second World War, the entire town of Moissac conspired to keep some 500 Jewish children from the grasp of the Nazis and compliant Vichy government officials.

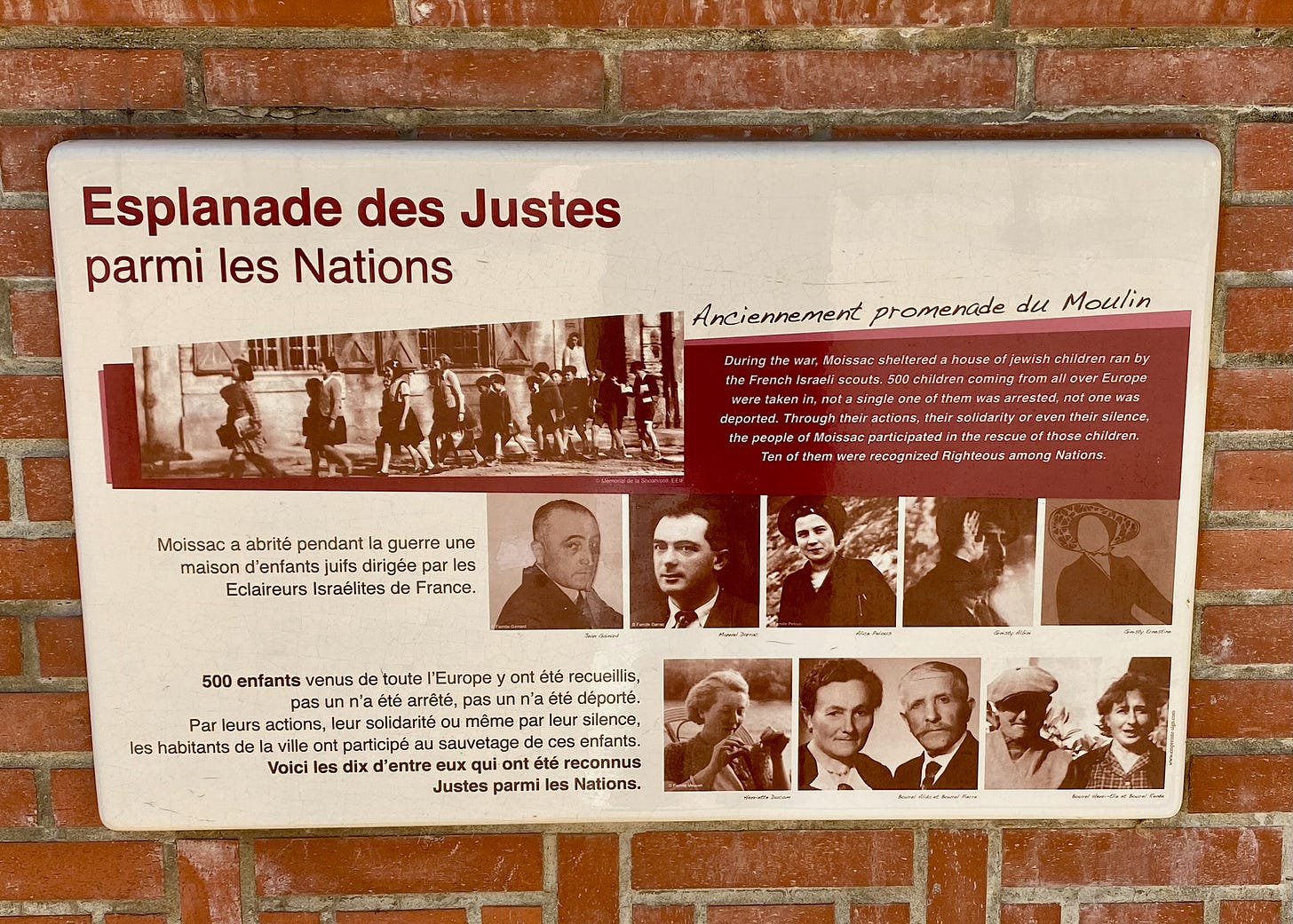

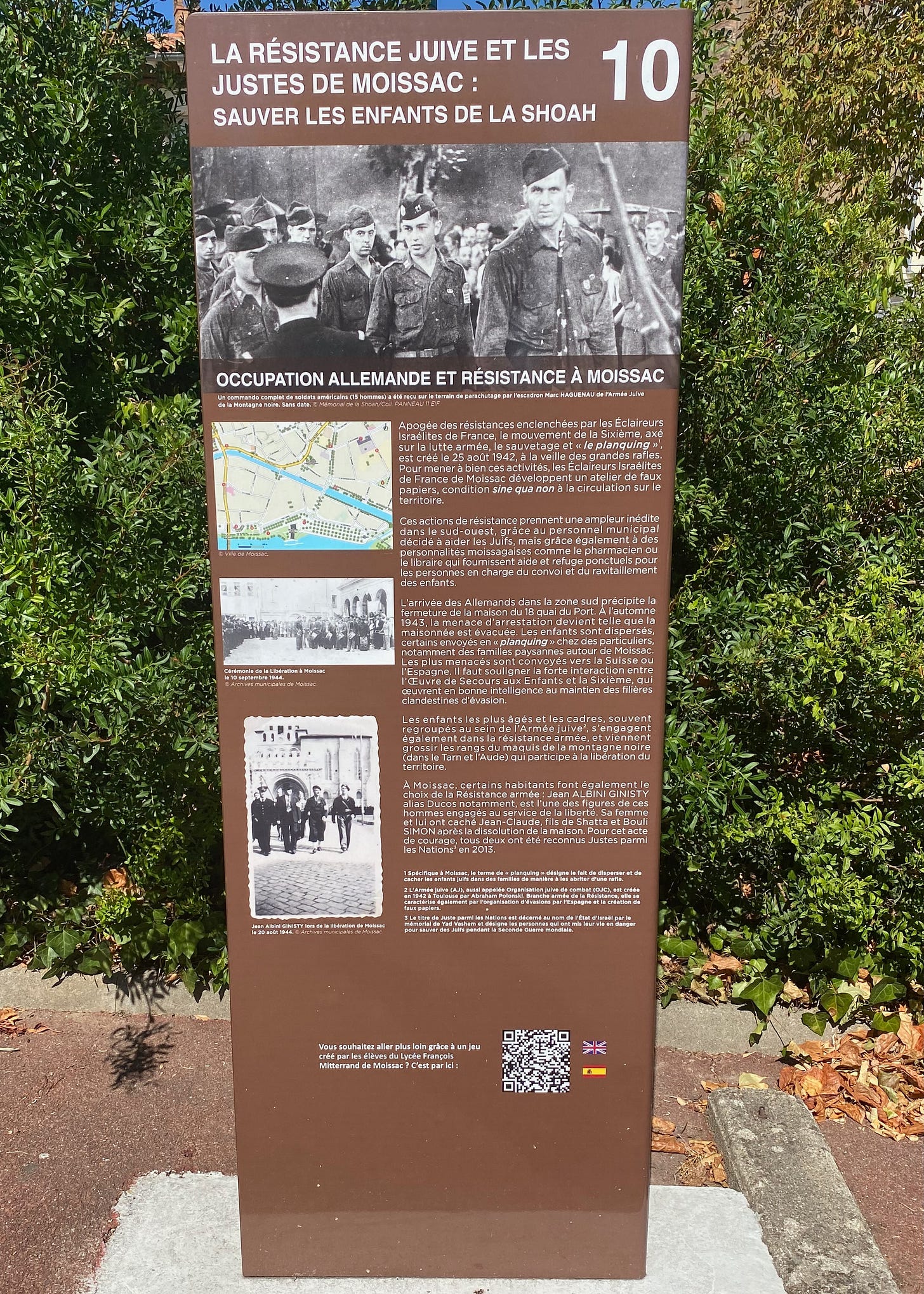

Hundreds of children—orphans and refugees fleeing from the spreading pogroms in Europe—were brought to Moissac starting in 1939 by a scouting movement known as the Eclaireurs israélites de France, run by Moissac couple Shatta and Bouli Simon.

Far from hiding what they were doing from locals, the townfolk were recruited in the deception. The children, who lived together at the Maison des Enfants, were encouraged to openly practice their religion and could be seen walking to the public baths every Friday to get ready for sabbath, singing Lève la tête, peuple d'Israël as they went.

But the residents knew what fate would await the children if they were discovered, so from Day One they were told to only speak in French (one-third were French, but many were from Germany, Poland and Hungary), false papers were created, and the older children were apprenticed to local tradesmen and merchants. As the danger mounted late in the war, the Simons received advanced warning from local police in 1943 of a planned raid and the children were scattered in the surrounding community, living among local families.

When the sanctuary was lifted later that year, not a single child had been captured or deported, another miracle for the town of Moissac, which is considered “the city of the Righteous Among the Nations,” a title used by Israel to honour non-Jews who put their own lives at risk to save Jews during the Holocaust.

Not far from the original site of the Maison des Enfants along the banks of the River Tarn, the town in 2013 inaugurated the Righteous Among Nations Square to honour the heroism of the population and to highlight this “forgotten” chapter of European history.

Ironically, the town’s current mayor, Romain Lopez, is a member of the far-right Rassemblement National party founded by Marine Le Pen. He is a proponent of ethnic nationalism has been accused of anti-Semitism for remarks downplaying statistics on its prevalence in modern France. “The apostles of the persecution complex don’t know what to invent next,” he wrote about remarks from Jewish scholar Serge Klarsfeld to the French parliament.

⚜ ⚜ ⚜

Putting aside the history lessons, Moissac is a quiet and quaint little town in the middle of fruit country, surrounded by thousands of hectares of melons, apples, grapes, cherries and plums. Popular with cyclists and hikers, the town is also a gateway to the confluence of the Tarn and Garonne rivers.

A picturesque town square in front of the St-Pierre Abbey offers a selection of restos and cafés, and I highly recommend a long walk along the Canal Latéral de la Garonne, a tree-lined waterway still used by pleasure craft that negotiate its still operating locks and rotating bridge.

And if you can make it here by October 4, you definitely have to catch the Fragile Beauty photo exhibition that my friend Charlie has organized. Located on three sites around town, it is a testament to the fragility of our environment as captured by six talented photographers.

⚜ ⚜ ⚜

For further reading, if any of the above has caught your interest, try these sources:

The wonderful Join Us In France Travel Podcast, which I think I’ll be using quite often myself after discovering it Tuesday, has an episode on Moissac that expands on some of what I’ve described here. The Toulouse-based hosts are convivial and well-informed and it’s an easy-listening hour.

For information on the Way of Saint James pilgrimage history and routes, including the most popular one (France’s), this site has it all covered.

And who wouldn’t want to dig deeper into the relationship between the Catholic Church and the French Revolution? Off with their headgear, as premier Legault might say! (Just don’t mess with our heritage, wink, wink.)

For the Saint Pierre Abbey, the abbey’s own website is unfortunately quite primitive, but I will include it here in the hopes that some of you might encourage them to update to Windows 7. The Wiki entry for the abbey is much more comprehensive, with lots of historical and political background that informed much of my description here.

There are several good sites (in French) delving into the forgotten heroism of the Moissagais during the Nazi occupation of France. Shoah: le miracle oublié de Moissac by Anne Rosencher beautifully captures the emotions of the time and the courage that it took to defy the occupiers and complicit French officials. For more history and testimonials from surviving witnesses, check out Moissac, ville de justes oubliee. And, finally, for the controversy over Moissac’s current mayor, I offer, in English, the Times of Israel’s report: French town that saved Jews elects mayor from party founded by Holocaust denier.

Thanks for accompanying me on my weekend in Moissac. And please don’t hesitate to join in the conversation or to suggest subjects for me to treat in future epistles!

See you on le weekend!

* If you’ve seen the movie The Name of The Rose, based on the Umberto Eco novel, the unnamed abbey’s front entrance was reportedly modelled on the Saint Pierre tympanum, which means the area between the lintel over a doorway and the arch above.

I enjoyed reading this, Peter. I had never heard of the town of Moissac before.

Great article.

Been reading them all.

Keep em coming.