The rain in Spain is mainly ... infrequent

Luck was with me on my ad-hocation in Andalusia, with great weather and plenty of great things to see despite not booking the top sites in advance

My trip to Spain was whimsical, by which I mean it was planned on a whim. That’s not the best way to see one of Europe’s most popular travel destinations, where top attractions are often booked as far as a year in advance. In Sevilla, for example, if you hadn’t booked months before, tickets to visit the Alcazar Palace or the Santa María de la Sede Cathedral were available only after waiting in a queue that would sometimes take an hour or two to navigate.

I don’t know about you, but waiting in line to go to church was my least favourite activity as a Catholic child. As an atheist adult, I’d rather queue up for opera tickets.

Early May is actually a great time to visit Spain tho. The Andalusian region sees 300 days of sunshine a year and average highs from June to September range from 32C to 36C. And that was before record-setting heatwaves brought to you by climate change. Last year, Sevilla averaged 38.5C in July, and hit 41C on July 19.

But I bet the lines were short. Except for gelato.

In the present, a lot of tourists had also figured out that May was a perfect time to visit, so Sevilla was extremely crowded. It was so bad that most tourists were overheard complaining about the tourists. The squares and restaurants were packed, boats and buses crammed with visitors, but cash registers were ringing happily across the land.

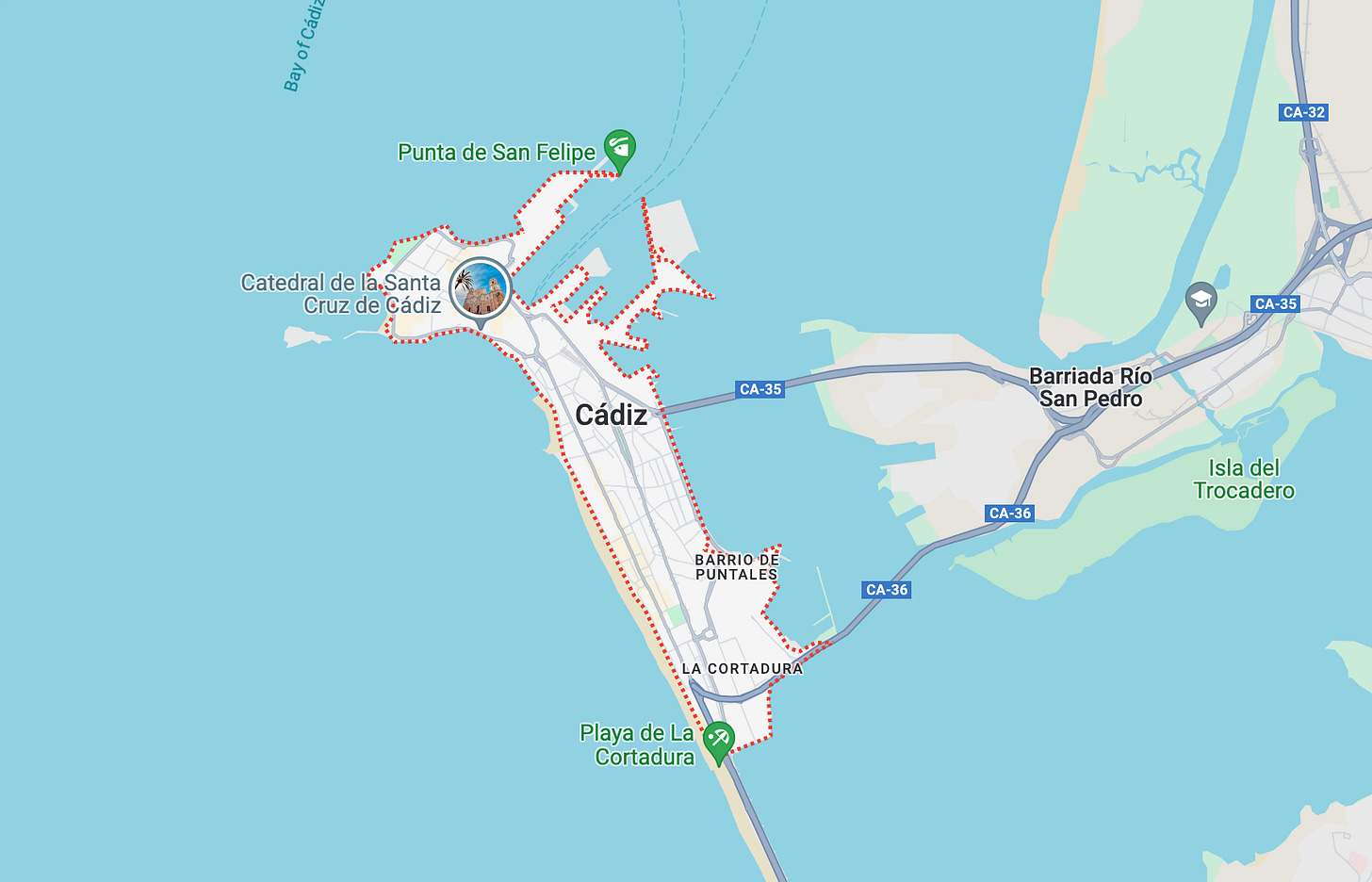

Personally, although I loved the La Banda Rooftop Hostel where I had luckily landed despite my lackadaisical “planning,” I needed to escape Sevilla after a few days. Taking up the recommendation of hostel staff and several of my fellow guests, I rescued my rental car from its parking dungeon and headed to Cádiz, an ancient port town on the Atlantic side of the Straight of Gibraltar.

(Don’t worry, I will return to Sevilla in an future dispatch.)

I knew nothing about Cádiz before heading out on the 120-km drive except it was famous for its long sandy beaches and busy port. I’d learn that this was the place that Columbus chose to begin two of his voyages of conquest in the Americas, and it had been one of the wealthiest cities thanks to its busy and, at times, well-defended harbour.

Some call Cádiz “Europe's oldest continuously inhabited city,” but that’s hyperbole, just ask Plovdivchanin or Argives. Let’s call it Western Europe’s oldest city, founded by Phoenicians around 1100 BC.

Cádiz is well-known for its annual February-March Carnival, an 11-day saturnalia of satire, sarcasm and conspicuous consumption. But the Cádiz I saw was a more sober cousin, busy but not boisterous, a welcome change from the packed streets of Sevilla.

It’s a small city, just 12 square kilometres, and the old quarter is easily walkable and full of shops and a huge variety of restaurants. When I say old, I don’t mean Phoenician old, of course. Cádiz was such a valuable city in such a key location that it was conquered and razed and rebuilt many times over the centuries. The heritage buildings to be found today date mostly from the 18th century, when sandbars on the Guadalquivir River forced the Spanish government to shift its American trade back to Cádiz from Sevilla, ushering in a yet another golden age for the city that had known many.

For example, it was the home port of the Spanish fleets bringing back stolen treasure from the Americas in the 16th century, which made it a popular target, especially of the British, who captured it more than once and burned it down, deliberately, at least once. Fortunately, much of it had been burned by accident 27 years earlier.

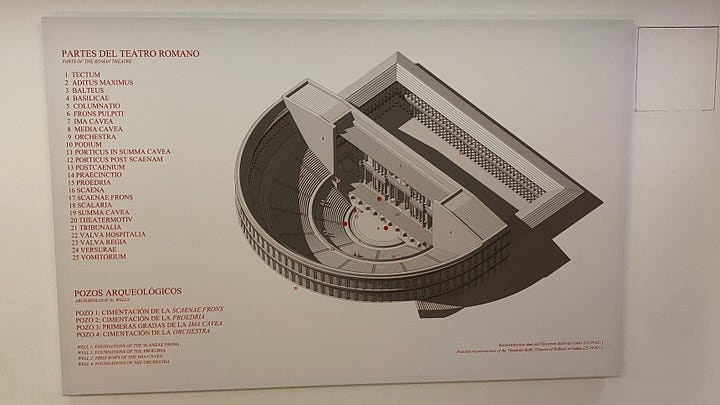

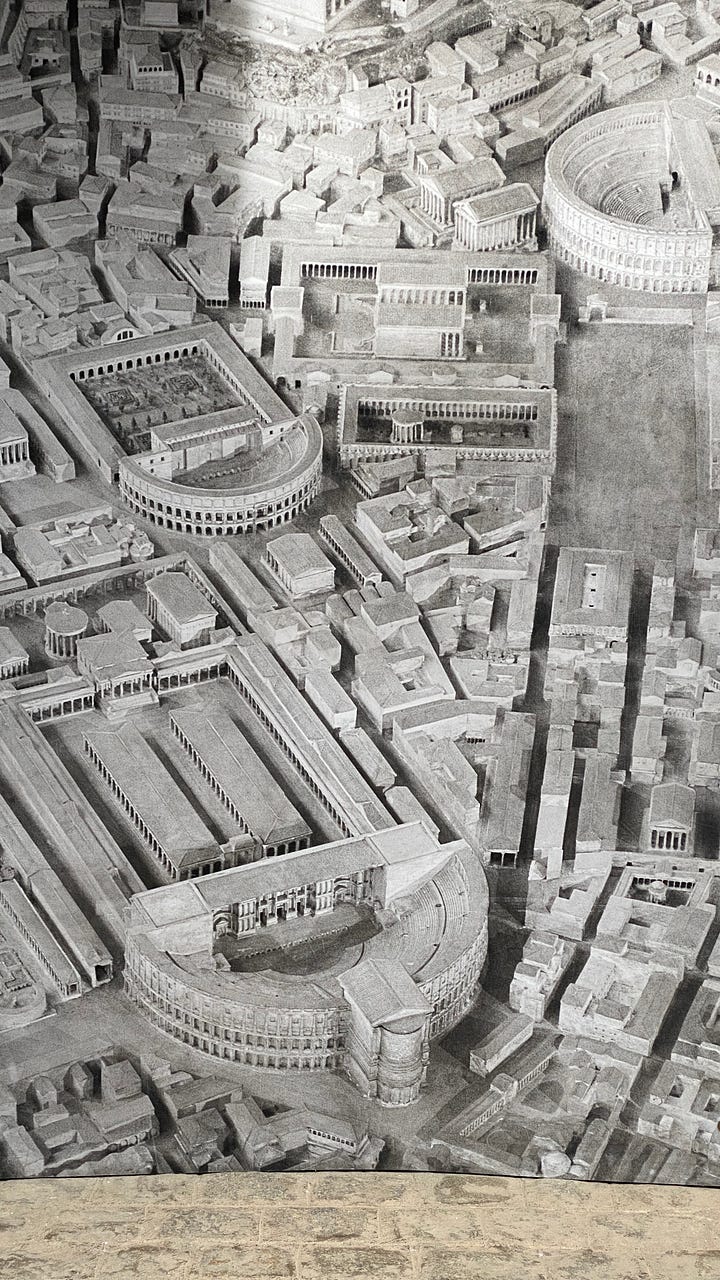

One historic building that did survive under the rubble of repeated conquests (Visigoths, Moors, French, English) is an ancient Roman theatre that it is estimated could seat 10,000 spectators, or about 10% of the current population. It was only uncovered in the 1980s during some public works excavations and was then partially excavated and restored with a museum detailing its design and construction.

The theatre was built with a local material known as oyster stone, a blend of seashells, sand and rock (see photo 3, above) formed over millennia. It was found in abundance here and was used in the construction of wealthier homes where the owners realized it didn’t burn as readily as wood. It was also good for building defensive structures such as the Castle of San Sebastián, constructed in 1706, and, in 1860, a causeway connecting the castle to the city.

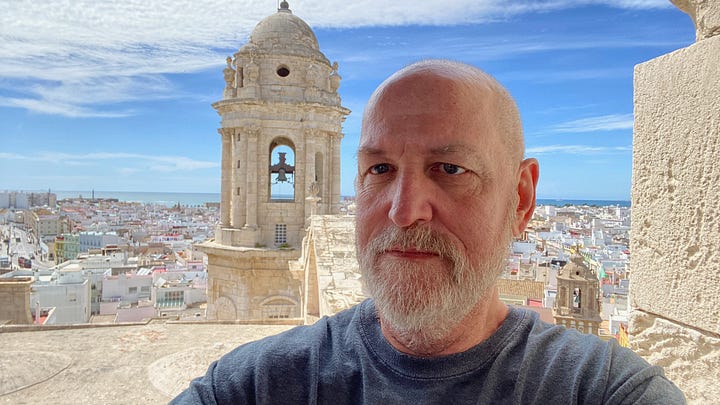

And, of course, Cádiz has a cathedral. Actually, it has two, since the old one was deemed not worthy enough during one of those golden eras I mentioned earlier. So the movers and shakers (i.e. merchants and priests) decided to build a monument to god suited to such a great city, but kept running out of money. It took 116 years to complete, from 1722 to 1838, and the design would change as it was being built, starting as baroque, then rococo elements were added, and finally it was completed in neoclassical style.

The moral of the story, if you go baroque, don’t go broke.

I really enjoyed Cádiz and could go on for a few more pages, but I will leave you instead with a few more photos and a recommendation for a free walking tour with Pablo Alvarez of Cadizfornia Tours. He is very proud of his native city and has an broad knowledge and engaging style that keeps you entertained for the nearly two hour walk through the old town and market.

I’ll be back mañana with the next installment of my tales of Spanish adventure. Thanks for riding along on my quest.