Sometimes a story is just too good

I'm staying near the intersection of Monplaisir and Soupirs, not far from the Allée des Demoiselles. Connection or coincidence? Let's find out …

I am currently staying in the Monplaisir district in Toulouse. When I first encountered Boul. Monplaisir in September, I had paused my bike ride at the intersection of the Allée des Demoiselles. Could it be, I wondered? Was this once Toulouse’s red-light district?

Adding to the intrigue, my current abode is right beside the Allée des Soupirs, so I asked my host about it. Was there a connection? She had no idea, so I planned that at some point I’d look up the origin of all these names.

(For those who don’t speak French, the words mean My Pleasure, Damsels and Sighs.)

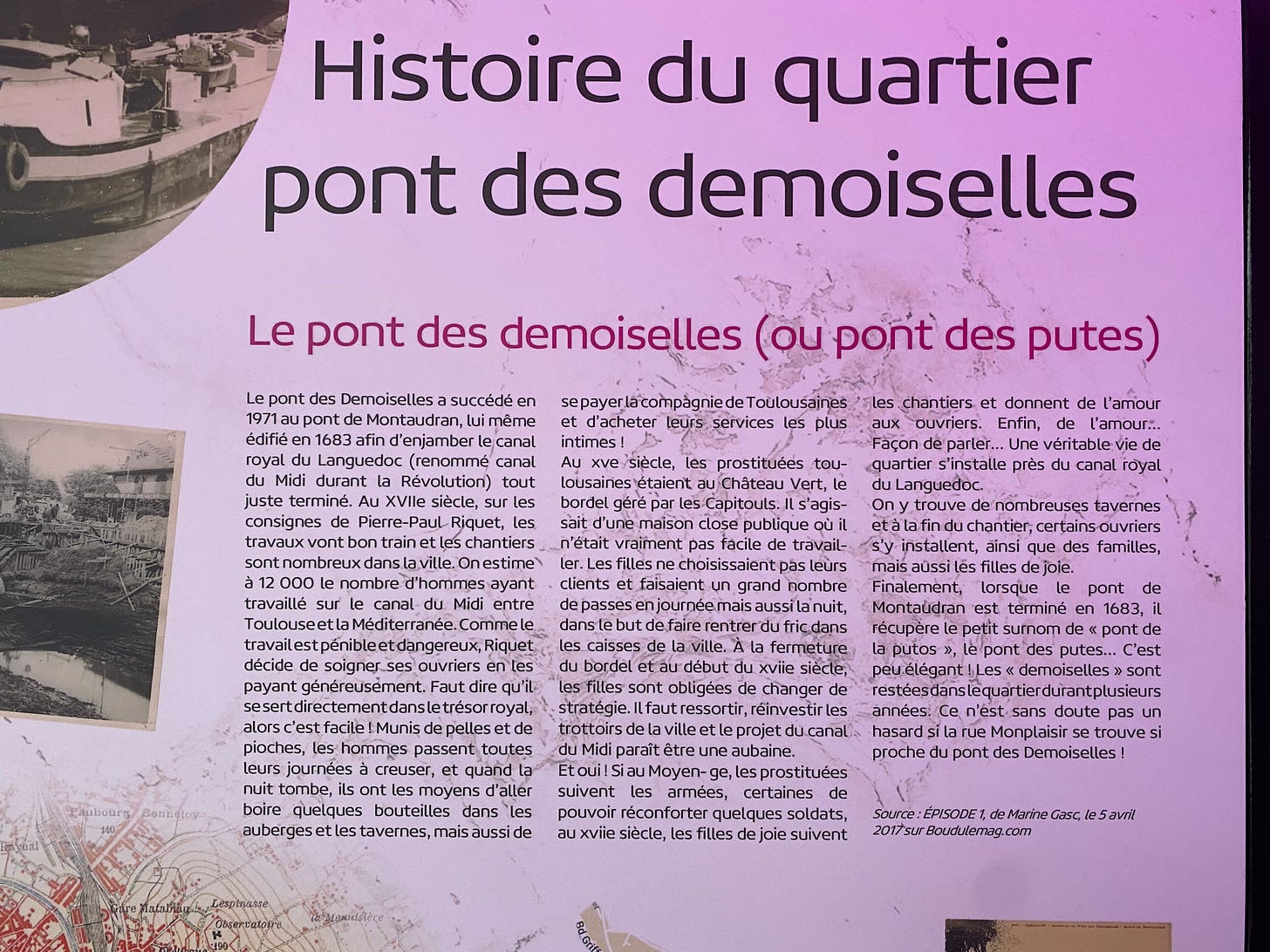

No need, however. The other day I went to a laundromat just off the Pont des Demoiselles and inside was a poster covering just that subject. It confirmed my theory about Monplaisir and Demoiselles, explaining the latter was familiarly known, after the bridge was completed in 1683, as the “Pont des putes” (whores). During the massive construction project to dig the Canal du Midi from Toulouse to the Mediterranean from 1667 to 1681, thousands of labourers were drawn to the city. They were very well paid for the era, so it wasn’t long before the area was flooded with taverns and sex workers, the poster explained. The workers would dig all day, then drink and debauch in the neighbourhood night spots once the sun went down.

At least that’s what the sign said.

Although the poster looked much like the city of Toulouse’s official interpretive panels, let’s keep in mind this was a laundromat, not a museum. The source cited for this excited speculation was an article by amateur historian Marine Gasc, published April 5, 2017, in Toulouse’s Boudu magazine. But I knew enough about the construction of the canal to know that at least one of the author’s statements was wrong. (She attributes the generous wages to the bounty of the royal treasury when in fact it was canal builder Pierre-Paul Riquet who set the working conditions, and 20 percent of the funding came from his own pocket. He was deeply in debt when he died seven months before the canal opened, so much so that it took his descendants 50 years to pay it off.)

So I dug a little deeper and, sure enough, I’m not the first to draw salacious conclusions from what appears to be little more than happenstance. French photographer Loic Tripier was also curious about the origins of Demoiselle, Monplaiser and Soupirs and wrote, not long after Gasc’s essay, that “at first glance, one might think that it was a hot neighbourhood, but as soon as one begins to dissect the name of these different streets, one understands that this succession of streets is only a coincidence.”

Tripier’s research revealed that Monplaisir was the name of a wealthy 18th-century family’s estate, located near the canal. The street running parallel to the canal would only take the name in 1908, more than 200 years after Midi workers had engaged their last demoiselles. As for the Allée des Soupirs, no one seems to know why the term was chosen in 1806 as the new name for west portion of the Chemin de la Baraquette, which had been dissected by the canal. Coincidentally, Baraquette was previously called Chemin de la Fontaine de l’Amour— but only for one year!

And what about Demoiselles? That was supposed to have been an attempt to give the putes nickname a less vulgar spin, but why would they bother to try rebranding a nickname? An alternative theory is that the canal attracted large numbers of damselflies, a common insect that breeds in southern French waterways.

But why let facts get in the way of a good story, eh? Bugs and the bourgeoisie don’t sell anywhere near as much as sex, sirens and sighs.

Gasc’s essay doesn’t even bother to make a case, simply stating that “it is probably no coincidence that Rue Monplaisir is so close to the Pont des Demoiselles!”

The moral of the story is … that even well-accepted histories are often held together with suppositions made by the story-tellers, and their persistence is ensured by the public’s desire to believe.

Even in this day and age where almost every event of significance is documented, recorded, photographed and videotaped, many people hang onto what they want to believe even when faced with evidence of its falsehood. (I think you know who I’m talking about.)

Just imagine how much worse it was when the historical record may be nothing more than a single wry note on a single city map about the Pont des Putes.

Sigh.