No safe harbour? Then build one!

The construction of two "Mulberry" harbours on D-Day beaches was an engineering and tactical marvel, planned in secrecy … and almost obliterated by a once-in-a-generation storm!

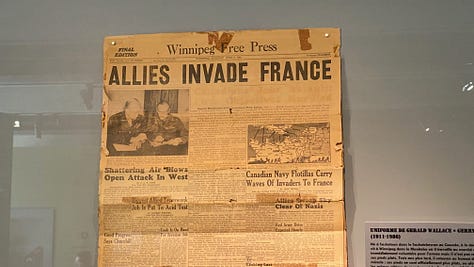

The disastrous raid on the French port of Dieppe in August of 1942 was a costly failure, especially for the 1,000 Canadians killed and 2,000 taken prisoner that day. Among the lessons learned was how difficult it would be to capture any of the heavily defended deep-water ports that the Allies would need for a successful invasion of Nazi-occupied France.

So if they couldn’t take a port, the Allies decided they would make one.

As incredible as it sounds, that’s exactly what happened less than two years later on two of the five D-Day landing beaches: the British Gold Beach and the American Omaha Beach. Codenamed Mulberry harbours, the components of the British-designed complex of breakwaters, piers, anchors and roadways were fabricated in secret on the English coast and were sailed, floated and towed across the channel, assembled and almost fully functional within two weeks of D-Day.

Then calamity struck. On June 19, the most violent storm to hit the Normandy coast in 40 years battered both Mulberry-A (Omaha) and Mulberry-B (Gold), turning the American pier into a twisted pile of steel and concrete. Mulberry-B was damaged but survived, thanks in part because the breakwaters and piers had been more securely anchored and were able to resist the tremendous storm. Mulberry-B would go on to serve for 10 months after D-Day, landing close to three million men, four million tonnes of supplies and half a million vehicles.

The engineering challenges of building a rapidly-constructed temporary pier that can withstand the onslaught of storms and provide a stable platform to offload tonnes of goods in constantly changing weather and tidal conditions must have seemed insurmountable. Yet British engineers were able to pull off the planning and construction of the component parts, most of which were invented for the occasion, in less than two years.

Eighty years later, the recent, short-lived, and costly attempt by the U.S. to build and operate an offshore pier on the coast of Gaza demonstrates just how difficult the task could be.

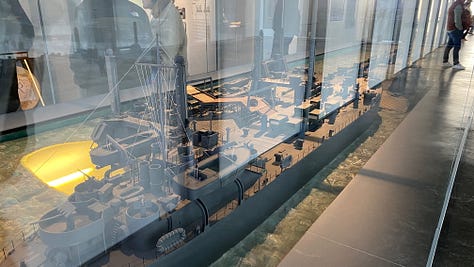

The Mulberry miracle is the highlight of one of the best museums I visited in Normandy, the Musée du Débarquement in Arromanches. This was actually the first Normandy war museum to be opened, in June 1954, and recently underwent a complete renovation and redesign. Crammed full of exhibitions and artifacts relating to the D-Day landings and Battle of Normandy, the intricate models of the Mulberry harbour and explanation of its origins and construction let visitors grasp the tremendous scale of the project.

A new animated graphic display of the harbour is accentuated by a projection of what the harbour looked like in 1944 onto windows overlooking the beach, melding real-life passers-by in a Second World War seascape.

Each component of the Mulberries has its own fascinating story, not to mention a weird nickname. Gooseberries, corncobs, bombardons, phoenixes, whales, beetles, kites and spuds all came together to form a working pier that could offload tanks and artillery as well as troops, ammunition and food. Even if the Germans had managed to intercept a message mentioning the Mulberries, they’d probably think it was a recipe for a strange British stew.

The corncobs were ships that would be sunk to form breakwaters known as gooseberries, which were combined with concrete “Phoenix” caissons and buttressed by a floating steel and rubberized canvas outer breakwaters called bombardons. Whales were connecting pontoon bridges supported by “beetle” floats moored by “kite” anchors. Finally, “spuds” were the landing wharves where the ships unloaded.

Even today, the remains of the concrete Phoenix caisson breakwaters still poke out far from shore and slowly deteriorating concrete shells of the beetle components lie scattered on the beach.

On the cliffs overlooking the museum and Arromanches beach, you’ll find two other D-Day sites. Since you’ll probably be using the parking lot up there anyway, the Arromanches-360 theatre offers a 20-minute film of archival footage from the landings to the bombing of Le Havre that will be a good primer before you walk down to visit the landings museum.

You should also check out the D-Day 75 Garden, which is no longer a garden but remains a memorial to British soldiers featuring veteran Bill Pendell, who landed at Gold Beach at the age of 22. A statue of Pendell at age 97 looks out a sculpture of his younger self and four other soldiers storming the beach. The sculptures created with welded metal washers are beautiful in their stark simplicity, yet enriched by the generous use of negative space that is filled with sky, sea, or grass, depending on which direction you’re looking. (Here’s a cool “making of” video by creator John Everiss.)

⚜ ⚜ ⚜

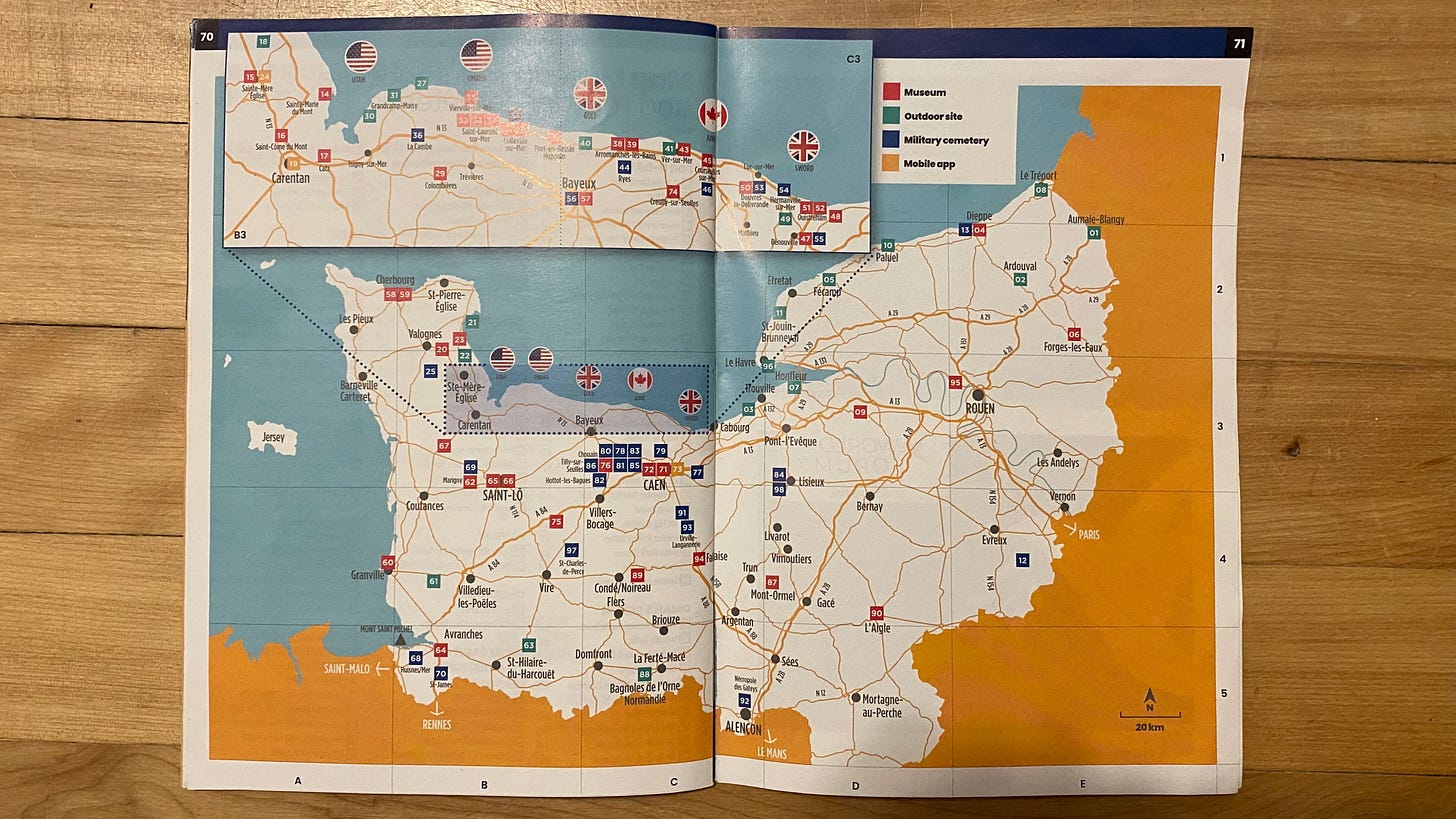

As I wrote just a few days ago, there are literally a hundred sites, monuments, cemeteries and museums related to D-Day and the 100 days of the Battle of Normandy. I managed to visit about a dozen of those and I’ve been sharing the best of that lot with you in my last few blog posts. I’m hoping to wrap that up with one more post this week, and will conclude with some advice from an expert on some of better sites I never got to see, for lack of time or awareness.

See you in a few days with the final chapter of my exploration of Normandy in the Second World War.