Millionaires and marble squares

The ancient Costa del Sol city of Málaga offers a wealth of art, heritage and conspicuous consumption

Pablo Picasso’s home town of Málaga, Spain, was known in its early days (circa 770 BC) as Malaka. Which if you know any Greek, is not something anyone wants to be called, at least not by anyone who knows Greek. Its location as a port city on the Mediterranean side of the Straight of Gibraltar made it an ideal trading site, however, so it attracted the usual rotating parade of conquerers, from Phoenicians to Romans to Visigoths, to Muslim Moors and Spanish Catholics.

You know, the usual suspects.

So it’s a city with deep historical roots, but a violent past that would, at one point, eliminate much of the population. This was the Great Replacement theory in practice, tho of course, as usual, it was the white Christians who were doing the replacing, starving out the city in an 1487 siege and then consigning the 11,000 surviving mostly Muslim Malagueños into slavery as floods of Christians poured in from elsewhere in the Iberian peninsula to take their place.

Yes, the conquerors were malakes.

Modern-day Malagueños, who like to call themselves boquerones (anchovies), are much more welcoming, especially when it comes to tourists, an important segment of the local economy. Málaga is a port of call for several cruise lines, but it’s also the home port of a 31 super yacht slips, whose docking fees of up to €2000 a day (about $3,000 Canadian) are higher than the average monthly take-home salary here.

Despite the draw for the super rich, don’t expect streets paved with gold, however. They are paved with marble. Everywhere you go in the pedestrian-friendly old city, the street tiles are make with local marble, which my walking tour guide was quick to point out “is not the good stuff.” Well, I’d hope not. It’s wonderful to walk on a surface with no potholes or unexpected bumps tho — except when it rains or a street cleaner has just passed, in which case you’d better have solid treads on your Birkenstocks or you could end up like the “La Manquita,” the nickname locals gave the Málaga Cathedral.

Manquita means the “one-armed lady,” a reference to the cathedral’s missing south tower, which was never completed even after 260 years of construction. It’s also, like many multi-century projects, the product of competing visions, with a Renaissance interior and Baroque exterior. It’s currently undergoing extensive renovation and restoration but, like Montréal’s Olympic Stadium, La Manquita will likely forever remain costly but incomplete.

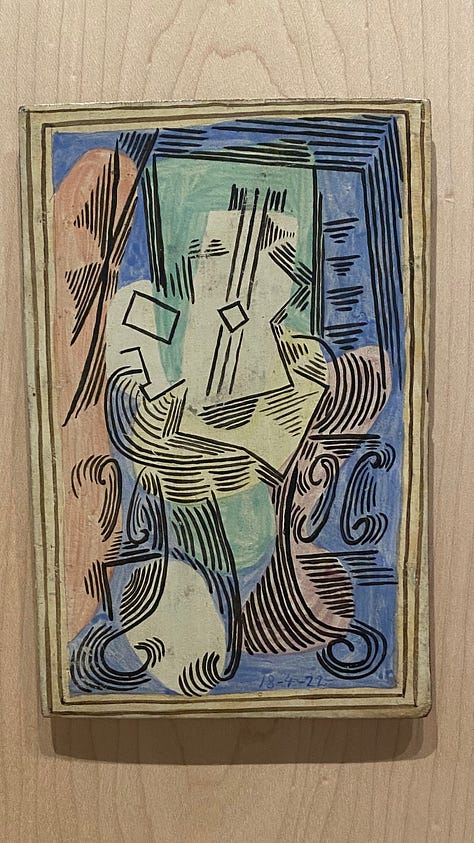

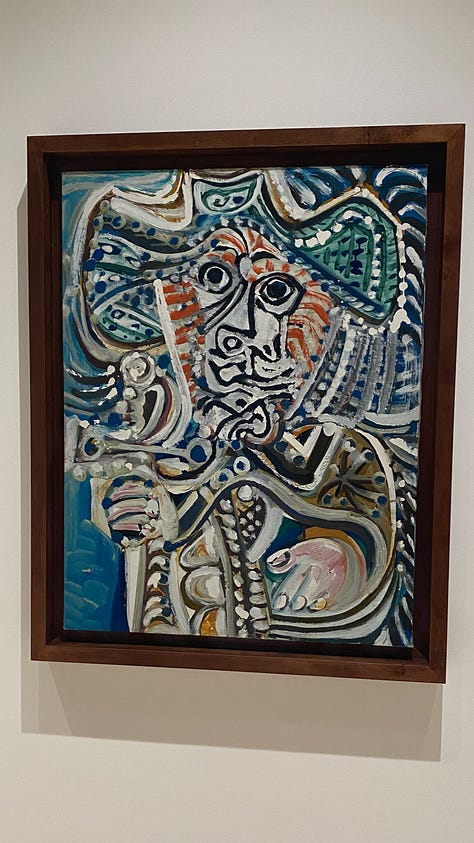

Museo Picasso Málaga, on the other hand, is expensive but undoubtedly the most complete collection of the artist’s work outside of Barcelona. Pablo Picasso: Structures of Invention. The Unity of a Life’s Work, contains 144 works that span eight decades, most donated by the artist’s family. For €12, “visitors [have] a chance to see relationships across Picasso’s career” and with different media, including oils, prints, ceramics and sculptures.

If you’re too square for cubism or you’re on a budget, entrance fees for the Alcazaba fortress and Gibralfaro Castle are only €5.50. Now if the name alcazaba seems familiar, it’s because it simply means citadel in Arabic, and the Málaga version is one of many you can visit in Spain or North Africa.

It’s no doubt one of the most impressive, however, begun in 1035 and expanded and renovated many times over seven centuries of Moorish rule. It was considered impregnable and indeed was never successfully breached. Not until a handful of merchants cut a deal for themselves to end the siege and opened the gates for the Spanish.

When Alcazaba ceased to have any military function in the 18th century, it was repopulated by poorer residents, who took many of the materials to build their own homes. It was only in 1933 that the residents were expelled and careful work began to restore and reconstruct the citadel and the castle according to surviving plans and using traditional techniques and materials. That’s why it seems to be in such amazing shape, much of it has been rebuilt and the work is still ongoing, with much of the citadel still off-limits to visitors.

Unlike Alcazaba, another historic part of the city has virtually disappeared. That is a pretty fancy trick, considering that it used to be a major river, running 47 km from the Camarolos mountain range to the Mediterranean.

As in many coastal cities, the Guadalmedina River was an important ecological and transportation resource, but human intervention eventually eliminated forest and wetlands along its banks that had helped control flooding and erosion. A massive flood in 1907 was the final straw, which saw mud and debris from upriver clog then destroy bridges, causing water in the historic city centre to rise as much as 5 metres.

The government’s solution for the flooding was the construction of a massive reservoir upriver to control the flow, so now the part of the Guadalmedina running through Málaga is dry pretty much all year round. It’s a scar that runs through the heart of the city and repeated electoral promises to renew the concrete canyon or replant forests have never been put fully into action. (If you want to know more, here’s a short video on the history.)

Sorry to end on such a sobering note, but it would be a depressing way to begin, now, wouldn’t it? So let’s get moving to our next Andalusian destination, Granada, one of the region’s most popular tourist magnets and the city where flamenco was born, not to mention the location of the famed Alhambra palace. See you there next week!