From beach to bunker

Many Canadians would become heroes in the Battle of Normandy, but many more would be haunted by what they saw—and sometimes by what they did—on the road to European liberation

With the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings looming, my one-week exploration of the Normandy coast in late May was of course dominated by a desire to better understand the import and impact of the Canadian contribution to the 1944 liberation of France. But I was also wrestling with the destruction of many French cities and the killing of thousands of civilians in the bombing raids conducted in towns like Le Havre and Caen. In those two cities alone, 8,000 French civilians are believed to have been killed by Allied bombs, of an estimated 20,000 French citizens killed in the Battle of Normandy.

As historian Christophe Prime put it in Histoire de la Normandie durant la Deuxième Guerre Mondial, “It was profoundly traumatic for the people of Normandy. Think of the hundreds of tonnes of bombs destroying entire cities and wiping out families. But the suffering of civilians was for many years masked by an overriding image, that of the French welcoming the liberators with open arms.”

The Allies were, of course, also responsible for the liberation of hundreds of million civilians in Nazi-occupied lands from Finland to Libya (280 million in Europe alone), but I think it’s critical to remember that it wasn’t only soldiers who paid the ultimate price for that freedom.

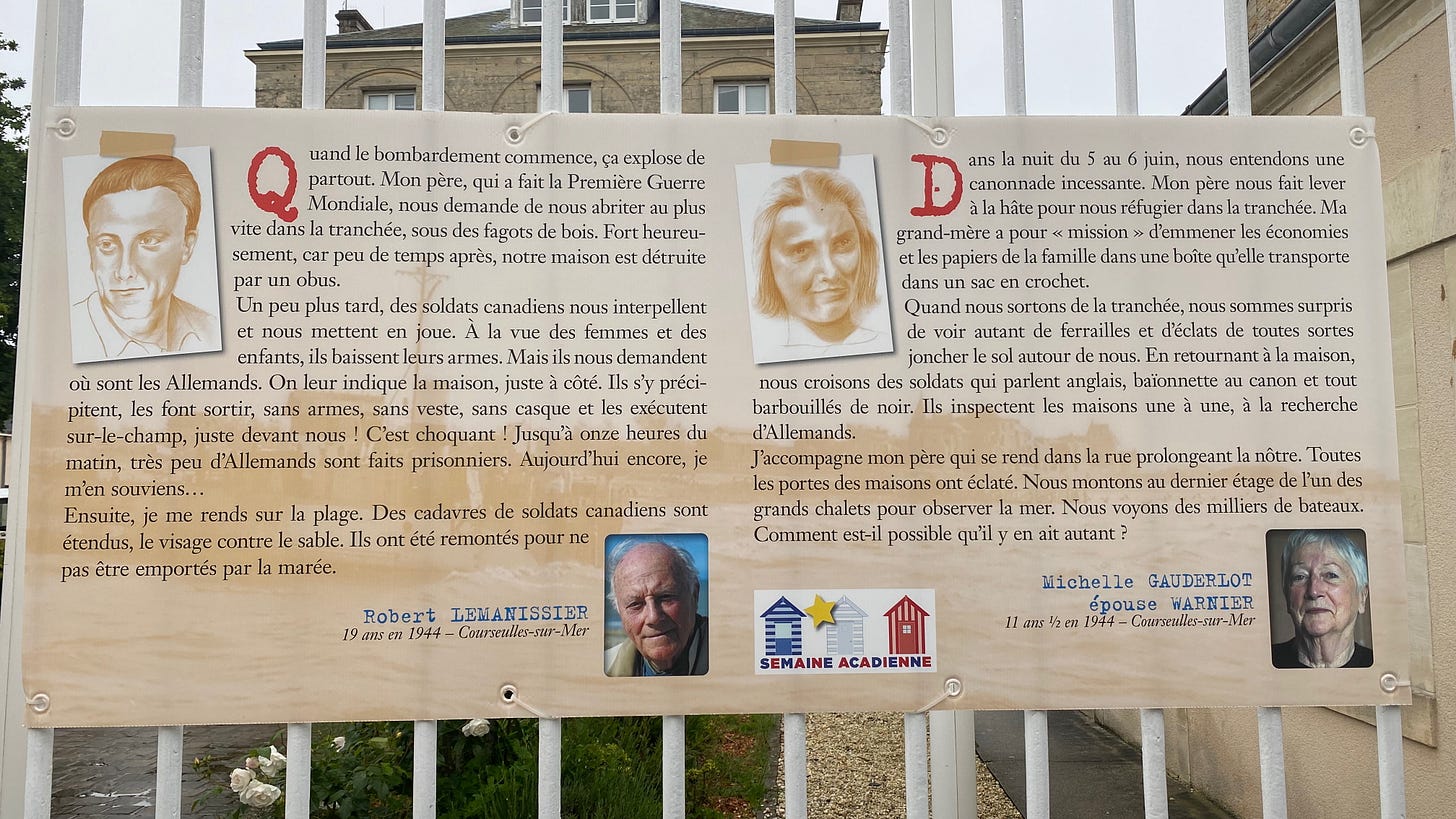

Eighty years later, the dark lining of that silver cloud is easier to find, even in the midst of D-Day commemoration. In one public testimonial on a billboard in front of city hall in Courseulles-sur-Mer (Juno Beach), I was surprised to read one witness’s rather brutal description of how some of our Canadian soldiers behaved after fighting their way ashore.

“A little later, we were called in by Canadian soldiers who put a gun to our heads. When they saw the women and children, they put down their weapons. But they asked us where the Germans were. We pointed to the house next door. They rushed in, took them out, without weapons, without jackets, without helmets, and executed them on the spot, right in front of us! It was shocking! Until 11 o'clock in the morning, very few Germans were taken prisoner. I still remember it today...

“Then I went to the beach. Corpses of Canadian soldiers lay face-down on the sand. They had been pulled up so as not to be carried away by the tide.” — Robert Lemanissier, 19 years old in 1944 — Courseulles-sur-Mer

The war crime of executing POWs was something the Germans were doing as well, of course, and these soldiers had just left hundreds of their comrades face-down in the sand. I don’t bring this up to vilify soldiers but to illustrate the evil that wars can inspire on all sides, exploiting man’s horrific ability to dehumanize both enemies and the “collateral damage” of those who get in the way.

So don’t expect my little essays on the various sites I visited in Normandy to wallow in jingoistic sentimentality. Although we all certainly appreciate the importance of the Allied offensive and the restoration of democracy and independence in western Europe, I can never consciously contribute to the glorification of war, no matter the cause, no matter how “just.”

⚜ ⚜ ⚜

The German attempts to fortify the entire Atlantic coast of Europe as far south as the Spanish border was an enormous construction project involving 260,000 workers (many enslaved) and 15,000 separate concrete emplacements, from small pillboxes to large command-and-control bunkers. The remnants of many of these installations remain even today, both as a reminder of the past and due to the impracticality of removing 17 million cubic metres of concrete.

Most of the emplacements have been closed off or sealed in, but some of have been preserved and are accessible to visitors. It’s pretty safe to say, however, that if you want to get an idea of what life was like inside one of these structures, there is no better site than The Grand Bunker Museum in Ouistreham, at the eastern edge of the five Allied landing beaches. A five-storey command-and-control structure that on a clear day could provide telemetry for German guns from Le Havre to Quinéville, the Grand Bunker was an important key to the wall, one that the Allies secured on Day 3 thanks to the stubborn efforts of Lieutenant Bob Orrell of the Royal Engineers and his crew of three men who managed to blast their way past the first armour-plated door in four hours.

To the young lieutenant’s surprise, the German captain immediately surrendered his 53-man crew to the four-man British demolition team. Stripped of any contents of worth, the building would remain derelict for more than 40 years until it was purchased by collector Fabrice Corbin, who not only restored the site but filled it with genuine German artifacts he had gathered.

Outside the building, the museum has a display of several large pieces of military equipment, including an M3 Stuart Tank and a rare example of the wooden Higgins landing craft the Allies used on D-Day (it was later lent to producers of the film Saving Private Ryan).

Inside, the visit of course begins with the requisite souvenir shop, but this one has an extensive collection of Second World War history books in French, English and German. (I often wondered what goes through the minds of German tourists as they tour the Normandy war sites. It seemed imprudent to ask, however.)

The bunker entrance begins in a long concrete corridor in the basement leading to a machine-gun emplacement ready to greet unwelcome visitors.

On the next level you’ll see a re-creation of the filtration room used to protect against gas attacks and keep the enclosed air safe from CO2 buildup. The second floor contained the living quarters, including bunks, dining room and infirmary, while the third and fourth houses the command-and-control centre, radio room, switchboard etc. Today the third floor is mostly devoted to information about the Atlantic Wall and D-Day exhibits. On the fifth floor you’ll find a large rangefinder that the Germans would use to pinpoint the location of Allied ships and, finally, a ladder leading to the roof where the Germans had mounted anti-aircraft guns.

Videos: views from the fifth-floor telemetry room and from the roof of the bunker. None of the buildings or structures you see in the background existed at the time of the landings.

Fabrice Corbin’s obsession with recreating the environment in which the Germans worked in the months preceding D-Day is what makes this museum so fascinating. The displays contain everything from grenade-launchers to tongue-depressors, and the third-floor museum would take hours to explore if you read every panel. You can get a real feel for what life must have been like for the soldiers and, ironically, their preparedness for invasion.

But if you don’t think you’ll be getting to Normandy any time soon, the museum provides you with an opportunity to take a virtual tour that will give you a good idea of what’s in store should you ever decide to go.

Speaking of going, that’s all for me for this installment of Sixty-something Solo. Thanks for joining me on this epic adventure and I hope to see you soon.

All text, video and photos © Peter Wheeland, 2024